I love sportswriting from the 1880s. Don’t you? Whenever I squint into my cellphone to check on the Pittsburgh Pirates or Steelers, I get the same formulaic narrative. It starts with the name of the impact player, followed by a meaningless statistic, followed impassively by the game changing event – all done with a third grade vocabulary. Today’s missive instead presents an entertaining account of a boxing match that involved your cousin pictured above, Aloysius Marx (1860-1931). He was the oldest son of Anton and Emma Fehrenbacher / Farabaugh Marx. He died alone at an infirmary in Galveston, Tx., and I wasn’t expecting much of a human interest story. But then I looked over his death certificate which listed the following occupation: acrobat. Acrobat??!? This is all I needed to fire up the whiz bang search engines on what my young son once called “the interwebs.” We don’t call it the internet anymore. We call it “the interwebs.”

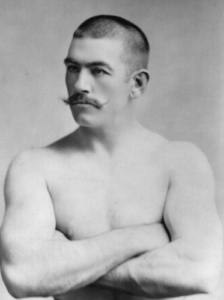

This is the famous John L. Sullivan. By acclamation, he was America’s first heavyweight boxing champion. This is the way he looked when he embarked on his “knockout tour” of the U.S. in 1884. He was 28-0 when he arrived at the Opera House in Galveston. His promoter offered $500 to anyone who could prevent being knocked out for four rounds. There were no takers after Sullivan’s exhibition. But the local barker who was sponsoring the event called out for Al Marx, who had a reputation as a fighter at the local docks were he loaded bales of cotton. The Galveston newspaper account of April 10, 1884, follows:

The Slugging Match. Another fair audience greeted the Sullivan contingent at the Tremont Opera House, which in a part was due to the announcement that Al Marx, a resident, though hithereto unknown, pugilist, had agreed to stand up before the scientific slugger for four three-minute rounds, or as much thereof as he was physically able to endure. Doubting Thomas. . . appositioned the coming to the scratch of the rash aspirant for p. r. fame, and confidently predicted a funeral, with the young man doing the hearse act, as the natural result of his temerity. Doubts of Marx’s non-appearance were not dispelled until the rising of the curtain, when both he and Sullivan were revealed advancing from opposite wings. All eyes were centered on Marx. To use the technical expression indicative of a superfluidity of adipose tissue, he was beefy. His chubby face and generally soft look excited a spasm of sympathy, as for a victim to be sacrificed, though the gloves were the softest of their kind and Sullivan had even expressed “that he was sorry for the young man and didn’t want to hurt him more than he could help.”

Though the same height the disparity in the physique of the men was striking, adding to the surprise elicited by Marx’s lead with his right, finding a resting place on Sullivan’s collar-bone. Sullivan then left go with his left, landing on Marx’s left eye. Though it staggered him, [Marx] managed to recover in time to let drive and fall short with both hands before another well-directed blow set him down. Lightly springing to his feet, he made a rush, got in a few slight body blows and again went reeling back with a bloody nose. On his feet again, and very groggy, Marx made another rush. A few short strokes [of] fighting, with Sullivan driving him before him, a dab at the right side of Marx’s stomach and three times down was scored against him. It required some effort for him to horizontalize; he was winded and had drawn up his whole right side. Sullivan advanced to him, motioned to strike him, but realizing the helplessness of his enemy, said: “Do you want any more?” “No,” was the gasping reply and this ended the bout. Time – 55 seconds. Considering the capabilities of Sullivan as a hard-hitter, Marx escaped with very light punishment, which consists chiefly of a slightly discolored eye. Marx says of his feelings when struck that they were like unto a man standing under a pile-driver encased by a foot-ball, and yet he thinks it such sport that he immediately matched with a local boxer, to meet him with hard gloves for a hundred dollars aside.

Al Marx’s 55 seconds of fame with the champion was parlayed into a career. He became known as the Texas Cowboy and he boxed (and brawled) all over the country. After the Sullivan fight, he beat a local hero in a 66 round contest that was watched by 800 paying customers. He had mixed results and mostly fought on undercards. In 1885, Al’s measure of fame for fighting Sullivan landed him in Madison Square Garden in New York. The Texas Cowboy began an undercard fight with Ike Williams of Bridgeport. When a “tip to the ribs” lifted Al into the ropes and angered him, hostilities resulted in heavy biting. After a separation the boxers would not cooperate in the next round, so the match was called off and the fighters ordered off the floor.

In September of 1886, Al had his finest hour in Omaha, where he fought for Nebraska’s vacant state heavyweight championship against Mike Fitzgerald. A round-by-round description shows that this was an excellent fight on the main card. Al staggered Mike in the first round, but had his nose bloodied in the second. There were mutual exchanges throughout but Fitzgerald was clearly flagging by the 6th. In the 8th, Fitzgerald could not get up after a ten count. Al received the state’s gold medal and was to receive all of the gate receipts for the 300 in attendance. Al later lost the title to a fighter named James McCormick. McCormick was losing when he suddenly broke Al’s jaw with a strong left glove that likely contained lead. The match apparently ended Al Marx’s boxing career.

Al’s life after this is hard to track because he became a cosmopolite. In 1892 he had a permanent residence in New York, yet he was in Paris applying for a passport as a professional athlete. In 1897, he appears as a professional strongman and weightlifter in London, where two accounts describe the hospital death of an adopted son, an accomplished acrobat. He then had three sons in three other countries (Spain, Portugal and the U.S.). By 1930, Al was a widower and patient at the St. Mary’s Infirmary, back were he started in Galveston, Tx. His brief obituary the following year gave no indication of his colorful past.

Al was born in Pine Township, Indiana County, Pa., the grandson of one of Cambria County’s five sibling immigrants, Michael Farabaugh (1810-1897). His family farmed for a time in Cambria County but left the area for Kansas. From there, Al winds up in Galveston, the site for this story’s main event – brought to you today, by the interwebs.

Thank you for taking the time to share this tribute of Al Marx on the interwebs. Al is my great grandfather. So took his three sons Manuel (my grandfather), Anton, and Luis and the rest of the family from port to port on a ship putting on the “Marx Brothers Flying Circus”.

Hello from France !

Do you know if Al Marx belonged to the Marx Brothers with the strongman John Grün “Marx” ?

If that is the case, they traveled together around the world and made a awesome show in Paris.

Best regards,

Nathalie

My name is Bart Black and Anton Marx is my grandfather. I also remember meeting Manual when I was small. We were in Galveston the other day and the story of the fight came up with my mom Patricia Marx. My wife found this story and I am very grateful. Thank you for writing it. It’s a great family read