St. Benedict Cemetery, Carrolltown, Pa.

For a school social studies assignment years ago, my daughter Sophie had to call my Mom in Cambria County and ask about her favorite childhood memory. Without hesitation, Mom told her it was the Memorial Day parade in Carrolltown, Pa. Our family albums have several pictures of those parades, as we waved miniature flags in our little boy sailor suits. Carrolltown is unquestionably the Farabaugh ancestral home in the U.S., and the entire town turned out for those parades.

We have scores of relatives who served our country all over the world. Because Memorial Day is set aside to honor the fallen, I collected those in the Farabaugh bloodline who lost their lives during wartime. There are just eighteen, but if I’ve omitted someone please let me know.

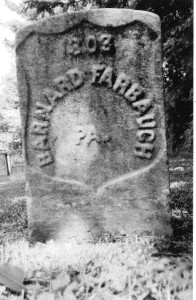

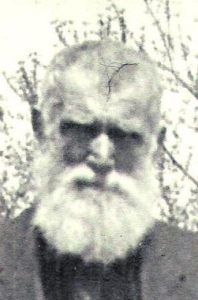

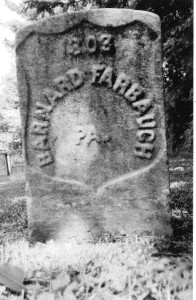

1. Bernhard Farabaugh

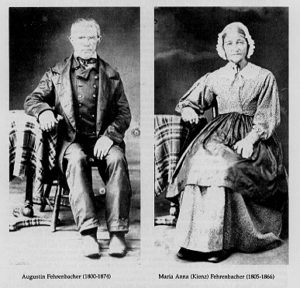

The Civil War service of Bernhard Fehrenbacher / Farabaugh (1835-1862) was very hard to understand because of a lot of misinformation in the Samuel Bates’ History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers and some confusing census records. It all cleared up when I pulled the file at the National Archives. Bernhard, sometimes known as Bernard or Barnard, was a Private in Company A of the 40th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, 11th Regiment Pennsylvania Reserves. He was mustered in for a three year term on June 25, 1861. The regiment was furnished and drilled at Camp Wright in Pittsburgh, and then marched to Harrisburg, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. It was assigned to General Meade’s 2nd Brigade of the Reserve Corps., and numbered 900 strong. It was ordered north to Great Falls, Md., in September of 1861, when the soldiers first saw action in a skirmish near the Potomac. The 2nd Brigade was held in reserve during the Union’s victory at the Battle of Dranesville, in December of that year. On March 10, 1862, the regiment advanced to Georgetown and Leesburg pike, and then camped in the rain at Hunter’s Mills. They then proceeded to Alexandria under a cold rain in what was the most difficult march the regiment was to encounter. They camped at Fairfax Seminary where many fell ill, and Major Litzinger’s health forced his resignation from service on April 1. It was here that Bernhard died in the Alexandria Hospital of typhoid fever on April 6, 1862. The condition is a bacterial infection caused by poor separation of food and drinking water from human waste. Over 27,000 Union soldiers died of typhoid fever.

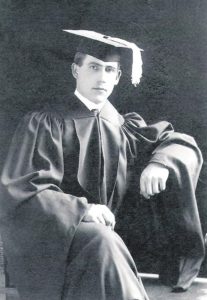

2. Walter Dominic Farabaugh

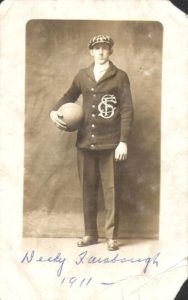

Walter D. Farabaugh (1893-1918)

The remains of Walter D. Farabaugh were the subject of the essay, Spooky Farabaugh Mystery No. 4, Whither Walter? He was raised in Carroll Township, Cambria County, Pa., and died in WW I. He was a corporal in Company H, 16th Infantry, First Division. Walter enlisted in May of 1918, arrived in France on July 30th, and was mustard gassed at Julvecourt, France, during the Battle of the Argonne Forest. He died the next day of pneumonia. Walter was buried in a temporary grave in France and his remains were removed and reinterred at St. Benedict’s Church in Carrolltown in 1921.

3. Alfred C. Reger (1891-1918) also died while engaged in the Meuse-Argonne offensive during WW I. Although Alfred died on the first day of that offensive, while with the 54th Pioneer Infantry, it is believed he died of disease rather than on the battlefield. He is interred at the local cemetery there.

4. John P. Reger (1894-1918), first cousin to Alfred, assigned to the 137th Infantry, also died during the Meuse-Argonne offensive (the largest and deadliest engagement in U.S. military history). He was killed in action either at the defense sectors at Gerardmer in the Alsace or at the Grange-le-Comte in the Lorraine. His remains came home to Page, ND, in 1921, where the American Legion Post is named after him today.

5. Marcellus James Sutton

Another Army soldier of WWI, Marcellus James Sutton (1897-1918), did not actually fight overseas. He reported for duty and was assigned to Camp Greenleaf, Ga., where he contracted broncho pneumonia. He died three weeks later in the medical camp facility at Ft. Oglethorpe. He is buried in my hometown of Loretto, Pa.

6. Jerome William Farabaugh

Jerome W. Farabaugh (1918-1944) served in the Army Air Force, with the 15th Airdrome Squadron in the Pacific Theater. As I understand it, these squadrons played in important role in building structures for airfields at strategic locations in the South Pacific after they were cleared. Jerome was likely assigned to this duty because his enlistment record shows he was “semi-skilled in electroplating, galvanizing and related processes.” This particular unit was active in the Admiralty Islands. Jerome died in a non-battle incident at his base. He “was fatally wounded when an explosive he was handling exploded.”

7. Herman J. Dinehart.

I never saw a headstone marked “cenotaph” before. It is a memorial that does not include the remains of the deceased. This one is in St. Lawrence, Pa. Herman Dinehart (1922-1944) also has a memorial marker at the Arlington National Cemetery. But the interesting thing is that there is yet a third marker at the Sicily-Rome Memorial Cemetery in Lazio, Italy. Herman was a Fireman, 2 Cl., on the USS Nauset (AR-89), a tugboat that gave extensive naval support in WWII along the North African Coast and Sicily. It continued with the Allied advance up mainland Italy and was attacked by the Luftwaffe during Operation Avalanche at the Gulf of Salerno, while attempting to clear mines. Although it did not have a direct hit from the German planes, a bomb landed close by and caused fires to break out and flooding occurred at a critical point below decks. A rescue operation ensued but as the tug righted itself and was reboarded a large explosion, split the USS Nauset in two. Naval histories attribute it most likely to a mine, but a niece of Herman states that the family believes it was torpedoed. Of the crew of 113, 18 were counted as dead or missing. Herman Dinehart was among the missing and his remains were never recovered.

I never saw a headstone marked “cenotaph” before. It is a memorial that does not include the remains of the deceased. This one is in St. Lawrence, Pa. Herman Dinehart (1922-1944) also has a memorial marker at the Arlington National Cemetery. But the interesting thing is that there is yet a third marker at the Sicily-Rome Memorial Cemetery in Lazio, Italy. Herman was a Fireman, 2 Cl., on the USS Nauset (AR-89), a tugboat that gave extensive naval support in WWII along the North African Coast and Sicily. It continued with the Allied advance up mainland Italy and was attacked by the Luftwaffe during Operation Avalanche at the Gulf of Salerno, while attempting to clear mines. Although it did not have a direct hit from the German planes, a bomb landed close by and caused fires to break out and flooding occurred at a critical point below decks. A rescue operation ensued but as the tug righted itself and was reboarded a large explosion, split the USS Nauset in two. Naval histories attribute it most likely to a mine, but a niece of Herman states that the family believes it was torpedoed. Of the crew of 113, 18 were counted as dead or missing. Herman Dinehart was among the missing and his remains were never recovered.

8. Leonard Gerald Sharbaugh

Leonard Sharbaugh (1924-1944) died at WWII’s Battle of the Bulge in Belgium and has memorial markers there and the one shown in Altoona, Pa. He was awarded the Bronze Star with Oak Leaf and had wartime assignments to the tank destroyer division at Camp Hood, Tx., attended radio school and then transferred to the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) at Louisiana State University. He however ended up in the infantry and apparently died as a foot soldier.

Leonard Sharbaugh (1924-1944) died at WWII’s Battle of the Bulge in Belgium and has memorial markers there and the one shown in Altoona, Pa. He was awarded the Bronze Star with Oak Leaf and had wartime assignments to the tank destroyer division at Camp Hood, Tx., attended radio school and then transferred to the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) at Louisiana State University. He however ended up in the infantry and apparently died as a foot soldier.

9. Frank Gilbert

Frank Gilbert (1925-1944) also died at the Battle of the Bulge. He enlisted in the Army on December 3, 1943. He trained at Ft. Knox, Ky., and at Camp George G. Meade, Md., before joining the 4th Armored Division, Company B, of the 35th Tank Battalion. He went overseas on May 15, 1944, and was killed in action on December 28, in Belgium. Frank was burned to death in his tank. He was only 19 years old.

10. James Knopp

James R. Knopp Jr. (?-1945) was the third relative killed at the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium. This is his marker at the Rue du Mémorial Américain there. James was a Corporal in the 509th Parachute Inf. Batallion.

11. Charles Barry

Charles Barry (1922-1945) was a WWII casualty following the twelve minute sinking of the USS Indianapolis (CL-35), torpedoed by a Japanese submarine between Guam and the Philippines, on June 30, 1945. It was the greatest loss of life for a single ship in the history of the U.S. Navy. Of the 1,196 crewmen, only 317 survived. It is believed that those victims who escaped from the immediate sinking died of exposure, dehydration, saltwater poisoning and shark attacks (the latter of which is famously recounted in the movie Jaws). Charles, a lieutenant, was not recovered and his name is inscribed in the ship’s monument in Indianapolis, Ind.

Charles Barry (1922-1945) was a WWII casualty following the twelve minute sinking of the USS Indianapolis (CL-35), torpedoed by a Japanese submarine between Guam and the Philippines, on June 30, 1945. It was the greatest loss of life for a single ship in the history of the U.S. Navy. Of the 1,196 crewmen, only 317 survived. It is believed that those victims who escaped from the immediate sinking died of exposure, dehydration, saltwater poisoning and shark attacks (the latter of which is famously recounted in the movie Jaws). Charles, a lieutenant, was not recovered and his name is inscribed in the ship’s monument in Indianapolis, Ind.

12. Joey Bishop

Joey Bishop (1933-1951) is the youngest casualty – just 17 years old. In the Korean War, you could volunteer at that age with parental consent. He was a Private E-2 in the 1st Calvary Division Infantry which went straight to the front lines of the conflict. Joey died as a result of a missile wound received in action on January 26, 1951. It was the second day of Operation Thunderbolt, a U.S.-led offensive that successfully forced Chinese forces to retreat to the Han River in South Korea.

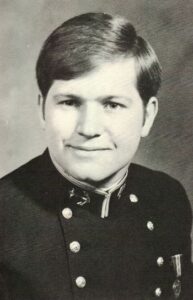

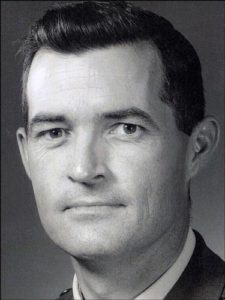

13. Charles Kohl Farabaugh

Charles K. Farabaugh (1929-1952) attended West Point. Our family had his distinctive wool uniform, which hung on a hanger in full view as I would chart the Farabaugh family as a teenager. Despite a close relationship between my parents and his, we didn’t know the specifics of Charles’ death during the Korean War. His story eluded me for years. There was some talk that he sacrificed his life in some dramatic way, like falling on a grenade. I only recently discovered the official account online: “The Distinguished Service Cross is awarded to First Lieutenant Charles K. Farabaugh, Infantry, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving as a member of an infantry company on July 17, 1952 in the vicinity of Haduch’on, Korea. Lieutenant Farabaugh led a combat patrol deep into enemy-held territory for the purpose of locating and probing hostile troops. The patrol was surprised by a numerically superior enemy force and a fierce fire-fight ensued. During the battle, Lieutenant Farabaugh observed an element of the enemy force moving slowly to the left of the patrol’s position in a flanking maneuver. After carefully estimating the situation, Lieutenant Farabaugh ordered the patrol to withdraw. He then moved from his protective cover through the intense enemy fire to a position from which he could cover the threatened flank. With complete disregard for his own safety, Lieutenant Farabaugh laid down such a withering hail of fire that the hostile forces were repelled. While he was covering the withdrawal of his patrol through the cleared sector, Lieutenant Farabaugh was mortally wounded.” Charles was brought home and buried in Carrolltown.

Charles K. Farabaugh (1929-1952) attended West Point. Our family had his distinctive wool uniform, which hung on a hanger in full view as I would chart the Farabaugh family as a teenager. Despite a close relationship between my parents and his, we didn’t know the specifics of Charles’ death during the Korean War. His story eluded me for years. There was some talk that he sacrificed his life in some dramatic way, like falling on a grenade. I only recently discovered the official account online: “The Distinguished Service Cross is awarded to First Lieutenant Charles K. Farabaugh, Infantry, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving as a member of an infantry company on July 17, 1952 in the vicinity of Haduch’on, Korea. Lieutenant Farabaugh led a combat patrol deep into enemy-held territory for the purpose of locating and probing hostile troops. The patrol was surprised by a numerically superior enemy force and a fierce fire-fight ensued. During the battle, Lieutenant Farabaugh observed an element of the enemy force moving slowly to the left of the patrol’s position in a flanking maneuver. After carefully estimating the situation, Lieutenant Farabaugh ordered the patrol to withdraw. He then moved from his protective cover through the intense enemy fire to a position from which he could cover the threatened flank. With complete disregard for his own safety, Lieutenant Farabaugh laid down such a withering hail of fire that the hostile forces were repelled. While he was covering the withdrawal of his patrol through the cleared sector, Lieutenant Farabaugh was mortally wounded.” Charles was brought home and buried in Carrolltown.

14. Myron Aloysius Farabaugh

Myron Aloysius Farabaugh (1929-1957) died near Nienburg-Weiser, Germany six days before his discharge from service. He was a passenger in a vehicle that was hit head on by a German truck. His widow Rita, in Cambria County, Pa., survived him by 58 years, succumbing in 2015. Myron was fond of German clocks and sent several home from overseas, which are still in use among family members.

15. Stanley A. Stys.

Pfc. Stanley A. Stys (1949-1968) was an infantryman in the 173rd Airborne Division during the Vietnam War. He was killed by small-arms fire in the Thua Thien Province of South Vietnam. He is buried at Grandview Cemetery in Johnstown, Pa.

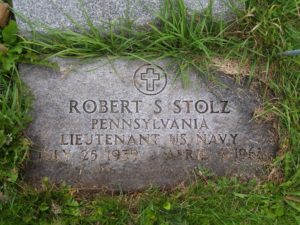

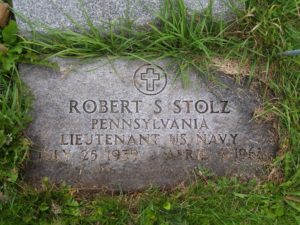

16. Robert Stolz (1939-68).

According to a 1988 newspaper article that profiled his parents’ 60th wedding anniversary, Robert Stephen Stolz (1939-1968) was a pilot and lieutenant in the U. S. Navy, missing in action after his plane was shot down in the Vietnam War on April 5, 1968. However, oddly enough, he’s not on the Vietnam Wall. He’s also not listed at the National Archives site. On the other hand, the Navy’s burial record references a death report and approved a cenotaph for St. Benedict’s Cemetery in Carrolltown. Whatever the unusual circumstances involved, it appears that Robert’s remains were never recovered, and that the headstone shown here is a memorial marker. He left behind a wife and three children.

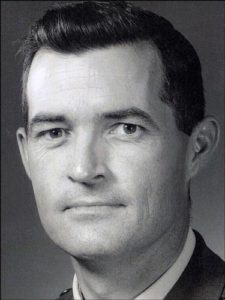

17. Col. Herbert O. Brennan (1926-1967, MIA).

17. Col. Herbert O. Brennan (1926-1967, MIA).

Col. Herbert “Bert” Brennan graduated from West Point in 1947 and became an Air Force pilot, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross while serving with the 35th Fighter-Bomber Squadron during the Korean War. He volunteered as a fighter pilot for the Vietnam War. On November 26, 1967, he was the bombardier on a F-4C, with Maj. Douglas C. Condit as pilot. The plane departed from Da Nang Airfield and was downed during its first pass in the vicinity of the Ban Karai Pass in a remote region of the Quang Binh Province of North Vietnam. It was downed either because of hostile fire (an unlucky “golden BB”), or a faulty bomb detonation fuse.

The wingman reported that the plane was seen to burst into flames, without any parachutes seen through the resulting thick smoke. No voice contact was made with the crew, although both of the plane’s beepers were detected, one of which continued over a two hour period, subsequent flybys to search and rescue met hostile file and were unsuccessful. Brennan and Condit were declared MIA and assigned to case 0928. Brennan was redesignated as Died While Missing, on October 18, 1974, and was included on the Vietnam Wall. The case was actively pursued for both airmen. In 1988, an F-4 crash site was found but could not be positively identified as the site of the Brennan/Condit plane.

In 1992, the investigation took a dramatic turn following the Vietnamese government’s release of the “Journal of AntiAircraft Combat; Military Region 4; From 1964-1973.” The 84 page report indicated that a diving aircraft on the correlating date was downed with one killed and one captured. A 16 member excavation team was deployed to the area. During a site inspection an unspecified “witness” miraculously produced an identification tag and led the team to a steep slope adjacent to a riverbed, where human remains were found. The remains were recovered along with several items that included survival kit components and evidence of a deployed parachute. These were the remains of Condit, which were repatriated in June of that year. Efforts continued to locate Brennan and the plane. In June of 1993, another F-4 crash site was found in the province at coordinates 48QXE2944521051, and this time there was positive identification when the aircraft data plate found was a match with the number one engine of the Brennan/Condit plane.

With both the plane and the Condit remains found, efforts continued to find Brennan. In 2000, an investigation team returned to the area of the 1993 discovery, but a broader search yielded no significant findings and no re-excavation was recommended. Various interviews were conducted of Vietnamese officials and former officers in 2005 and 2008, but these did not yield any additional leads. No new details have since emerged over the fate of Col. Herbert Brennan.

18. Capt. Stephen J. Burley (1954-1984). Capt. Burley was among 29 American and South Korean soldiers that died in a helicopter crash, attempting to return from an aborted exercise mission. The CH-53D chopper was attempting to return to a base in Pohang, South Korea under rainy and windy conditions when it crashed into a hillside. Capt. Burley was laid to rest at the Beverly National Cemetery in New Jersey.

The history of these soldiers is often forgotten due to passage of time. Memorial Day is meant to revive the sacrifices of these brave relatives, and remind us of the importance of patriotism and the freedoms that are all too often taken for granted. Our family has a contribution from Kane Farabaugh. Kane is a veteran who recently produced a documentary profiling a WWII soldier, The Greatest Honor. It’s good to know that one of our own maintains an active interest in, and has worked to preserve our military history.

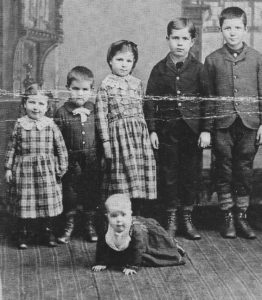

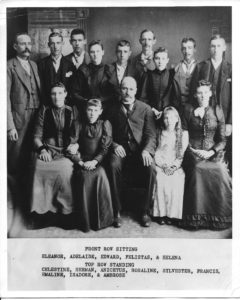

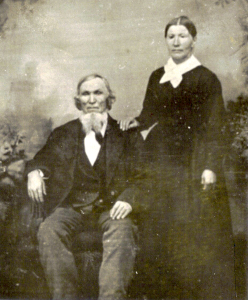

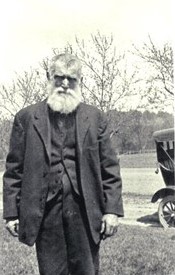

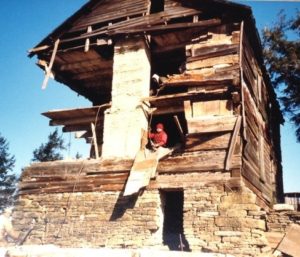

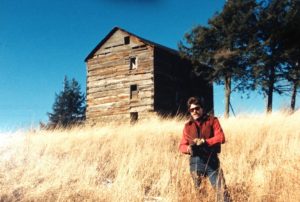

This photo of the ancestral home was taken in 1988, more than 20 years after it was last occupied. Hilda confirms that it resembles her childhood home, which by the time of this photo had fallen into its ramshackle, but still sturdy, state. It looks stark and foreboding. But as explained below, Hilda has clear memories of it in fact being quite a lively and joyful home, filled with children and headed by their hard-working and dedicated parents. It was located near Bradley Junction in Allegheny Township, Cambria Co., Pa. From the old “Brick Road” below, the farmland is accessed by an unmarked lane (now known as Beck Road) that opens to the left to another lane that leads directly to the site of the original homestead and pond. The land is spectacular, especially in the Fall. The tract at one time grew to 200 acres, and alternates from dense woods to squarely defined clearings that are now matted green grasses in the Spring and dry yellow in the Summer. If you were to visit it today, you can witness much of what Hilda and the immigrants experienced: green forests, the gently sloping fields set against powder blue skies, bird songs and the sound of winds through trees uninterrupted by humanity. The iconic images of the settlers Augustine and Mary come to mind when one stands in the middle of this sprawling property, and the imagination puts them in motion. This is the land that was painstakingly cleared of timber and then laboriously farmed for over a hundred years. It is the ancestral home to over 8,000 Farabaugh descendants today.

This photo of the ancestral home was taken in 1988, more than 20 years after it was last occupied. Hilda confirms that it resembles her childhood home, which by the time of this photo had fallen into its ramshackle, but still sturdy, state. It looks stark and foreboding. But as explained below, Hilda has clear memories of it in fact being quite a lively and joyful home, filled with children and headed by their hard-working and dedicated parents. It was located near Bradley Junction in Allegheny Township, Cambria Co., Pa. From the old “Brick Road” below, the farmland is accessed by an unmarked lane (now known as Beck Road) that opens to the left to another lane that leads directly to the site of the original homestead and pond. The land is spectacular, especially in the Fall. The tract at one time grew to 200 acres, and alternates from dense woods to squarely defined clearings that are now matted green grasses in the Spring and dry yellow in the Summer. If you were to visit it today, you can witness much of what Hilda and the immigrants experienced: green forests, the gently sloping fields set against powder blue skies, bird songs and the sound of winds through trees uninterrupted by humanity. The iconic images of the settlers Augustine and Mary come to mind when one stands in the middle of this sprawling property, and the imagination puts them in motion. This is the land that was painstakingly cleared of timber and then laboriously farmed for over a hundred years. It is the ancestral home to over 8,000 Farabaugh descendants today. Hilda was born here on July 22, 1917, as the 7th of 11 children to Ed and Mary (Baker) Farabaugh. In the cross-sectioned image, the worker in red is sitting in the window frame for the first floor parlor. That room was reserved for house guests. It had a black leather couch, a family photo album now lost to time, plants, ferns by the window, and a place for the Christmas tree.

Hilda was born here on July 22, 1917, as the 7th of 11 children to Ed and Mary (Baker) Farabaugh. In the cross-sectioned image, the worker in red is sitting in the window frame for the first floor parlor. That room was reserved for house guests. It had a black leather couch, a family photo album now lost to time, plants, ferns by the window, and a place for the Christmas tree.

I never saw a headstone marked “cenotaph” before. It is a memorial that does not include the remains of the deceased. This one is in St. Lawrence, Pa.

I never saw a headstone marked “cenotaph” before. It is a memorial that does not include the remains of the deceased. This one is in St. Lawrence, Pa.

17.

17.